Pulmonary Hypertension - Primary or Secondary

See

Pulmonary Hypertension

8/16/2005 AIM

SX | DX |

RX See

pulmHTN2007.pdf |

pulmHTN_Rx2007.pdf

|

pulmonaryhypertension2009.pdf

Pulmonary hypertension, generally defined as a mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 20-25 mm Hg, may be due to primary pulmonary vascular disease or may be secondary to various cardiac or pulmonary diseases.

SX of Pulmonary

Hypertension:

dyspnea, tachypnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, exercise intolerance, or syncope

of uncertain cause. Raymaud's phenomenon, arthritis, & positive

ANA test have been associated with Primary Pulmonary Hypertension.

Primary Pulmonary Hypertension (PPH) is considered an idiopathic, progressive

and fatal illness with an average survival of 3-5 years after onset of clinical

symptoms. The female to male ratio is 1.2 : 1, and 4.3 : 1 in the black

population. Most pts are young, with the highest frequency between

20 and 40 years.

PPH pts usually present with elevated systolic pulmonary

artery pressure of about 90 mmHg, and diastolic 45 mmHg (normal PA <30/15

mmHg)

Pulmonary Hypertension - Secondary

Possible Mechanism of pulmonary hypertension:

Pulmonary vasodilator therapy has not been useful for the treatment of any of the secondary types of pulmonary hypertension.

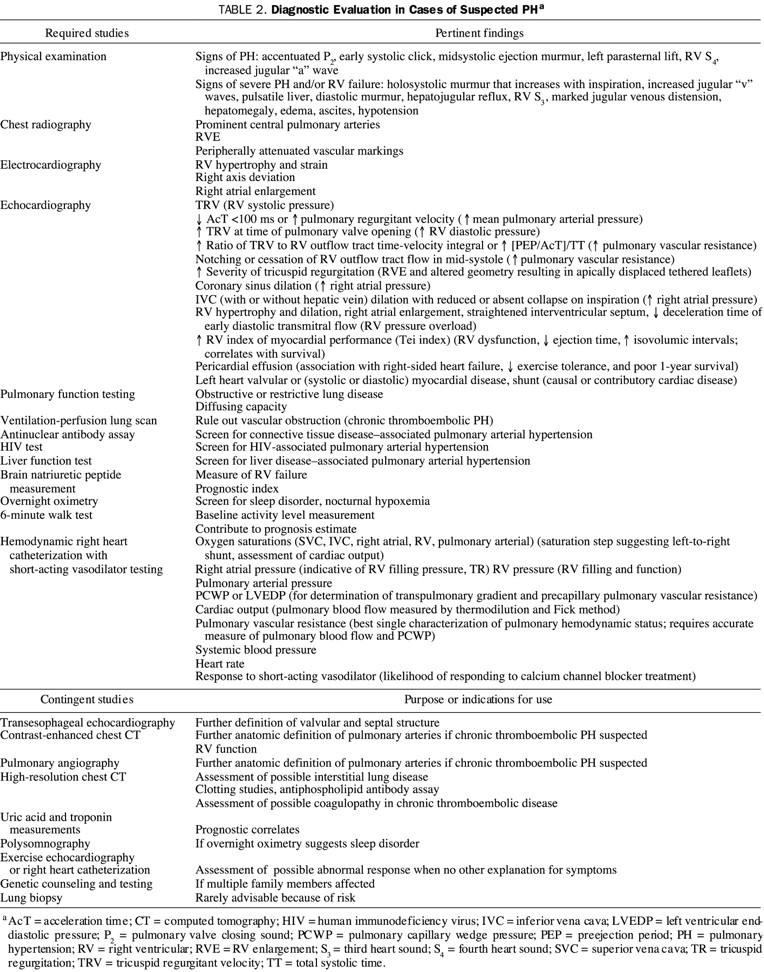

The diagnostic evaluation focuses on determining the severity of pulmonary hypertension and its cause. The standard diagnostic tests should include chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests, arterial blood gas, lung perfusion scan, pulmonary angiogram, and cardiac catheterization. An echocardiogram combined with Doppler studies allows the noninvasive evaluation of pulmonary artery and right ventricular pressures.

Determining the severity may be aided by echocardiography with continuous-wave Doppler methods, using calculations involving the velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation signal. Right-heart catheterization remains the definitive method for measuring pulmonary vascular pressures and is the only reliable technique if tricuspid regurgitation is not present.

REF:

ACP Library on Disk - © 1996 - American College of Physicians

Current Therapy in Adult Medicine 4th Ed, 1997 - Jerome Kassierer & Harry

Greene II

Primary

Pulmonary Hypertension. ACCP Consensus Statement. CHEST 104:236-250,

1993

General Approach to Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension 2009

Of the 6 main lines of treatment used for patients with PH:

1. Prevention.

Because some forms of PH have clear causal mechanisms, these risk factors

should be eliminated to prevent the development of PH. Repair of congenital

left-to-right shunt lesions before the evolution to Eisenmenger syndrome

is a notable preventive strategy. Efforts to increase societal awareness

of, and curtail the use of, the illicit use of methamphetamine and its

derivatives (eg, fenfluramine appetite suppressants) are likely to reduce

the future prevalence of toxic PAH.

2. Appropriate Screening of high-risk patients

for early signs of PH,

usually with carefully performed Doppler

echocardiography. High-risk patients include those who have a

family history of PAH, known genetic allelic variants associated with PAH,

connective tissue diseases (especially limited systemic sclerosis), and

congenital heart disease. Patients with symptoms of exertional dyspnea, angina,

or syncope should be screened for PH if other causes of the symptoms cannot

be identified.

3. Optimize therapy for any associated or

causal diseases.

Disease of the left side of the heart and its consequences (eg, blood volume

expansion) that can cause increased pulmonary venous pressure should be maximally

managed. Sleep disorders must be investigated and appropriately addressed.

Hypoxemia of any cause requires correction because of its vasoconstrictive

stimulus. Patients with airways disease warrant treatment with bronchodilators,

as well as early treatment for infection. In patients with chronic pulmonary

thromboembolisms, which may be a manifestation of a possible procoagulant

condition, treatment with anticoagulation and, in some cases, inferior vena

cava filters is required to reduce the chance of clot recurrence or progression.

4. Adjunctive, or supportive,

therapy,

which is directed to the consequences of PH. Death related to PAH is frequently

the result of right ventricular failure or arrhythmias likely related to

high right ventricular wall stress. Right ventricular decompensation can

also lead to peripheral edema, ascites, hepatic congestion, and intestinal

edema. After right ventricular failure occurs, aggressive management is required.

Sodium and fluid restriction are mandatory

parts of this management. Use of loop diuretics,

supplemented by metolazone, and potassium-sparing agents are necessary

in many patients. However, these medications must be used judiciously to

balance reduced intravascular volume and control of edema and ascites with

adequate preload of the ventricles to maintain systemic arterial pressure

and cardiac output.

Digoxin may be useful for inotropic support in some patients; however, its efficacy in cases of PH is unproven. Cases of advanced right ventricular decompensation may require inpatient management with intravenous inotropic support using dobutamine or milrinone.

Supplemental oxygen throughout the day, nocturnal positive pressure breathing, or both should be used to assure maximal daily duration of normoxia.

Hypoxemic patients should avoid air travel and visits to sites at high altitudes unless near normalization of arterial oxygen saturation can be achieved with supplemental oxygen. However, air travel with oxygen often requires special arrangements with the airlines. Although patients are often encouraged to perform normal daily activities and participate in supervised rehabilitation programs to maintain fitness, attempting aggressive exercise or weight-resistance activities is inadvisable.

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines should be given to prevent pulmonary infections. Early antibiotic treatment for upper respiratory infections is also warranted. However, vasoconstrictive medications (ie, decongestants) should be avoided.

Anticoagulation with warfarin is advised to manage PAH, as well as chronic pulmonary thromboembolism, on the basis of documented coagulation diathesis and reported survival benefits in patients with these conditions46-48 and histopathologic evidence of pulmonary vascular thrombosis in situ.49 An international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 2.5 is the goal for patients with IPAH or associated PAH, unless a bleeding risk or other contraindication is apparent.

5. The fifth line of therapy is vascular-targeted treatment directed at reversing or diminishing vasoconstriction, vascular endothelial cell proliferation, and smooth muscle cell proliferation.

VASCULAR-TARGETED TREATMENT

No current treatment approach to PAH provides a cure. Rather,

treatment goals are to reduce pulmonary vascular

resistance, pressure, and symptoms and to increase patient activity and

longevity.

Four classes of medications are available that act on the predominant recognized

pathobiologic pathways (Figure 1).

a. Calcium channel blockers reduce

the influx of calcium ions into pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, thereby

reducing calcium-mediated activity of the contractile mechanism.

b. Prostacyclin analogues supplement

deficient levels of prostacyclin caused by underexpression of endothelial

prostacyclin synthase.

c. Endothelin receptor antagonists

block the effect of endothelin at smooth muscle cell receptors.

d. Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5)

inhibitors promote the activity of the nitric oxide pathway by

reducing conversion of cyclic guanylate monophosphate (a second messenger)

to 5'-guanylate monophosphate (an inactive product).

6. If pharmacologic treatment fails, surgical interventions, the sixth line of therapy, should be considered. These last 2 lines of therapy are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Current

Concepts: Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension

Fedullo P. F., Auger W. R., Kerr K. M., Rubin L. J.

NEJM 2001; 345:1465-1472, Nov 15, 2001. Review Articles

Combination

Therapy with Oral Sildenafil and Inhaled Iloprost for Severe Pulmonary

Hypertension

Although limited by the small sample and lack of long-term observations,

the study shows that oral sildenafil is a potent pulmonary vasodilator that

acts synergistically with inhaled iloprost to cause strong pulmonary

vasodilatation in both severe pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic

thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Ann

Intern Med. April 2,2002;136:515-522.

The Mangement of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Cleveland Clinic J of Med April 2003 Special Issue

2009

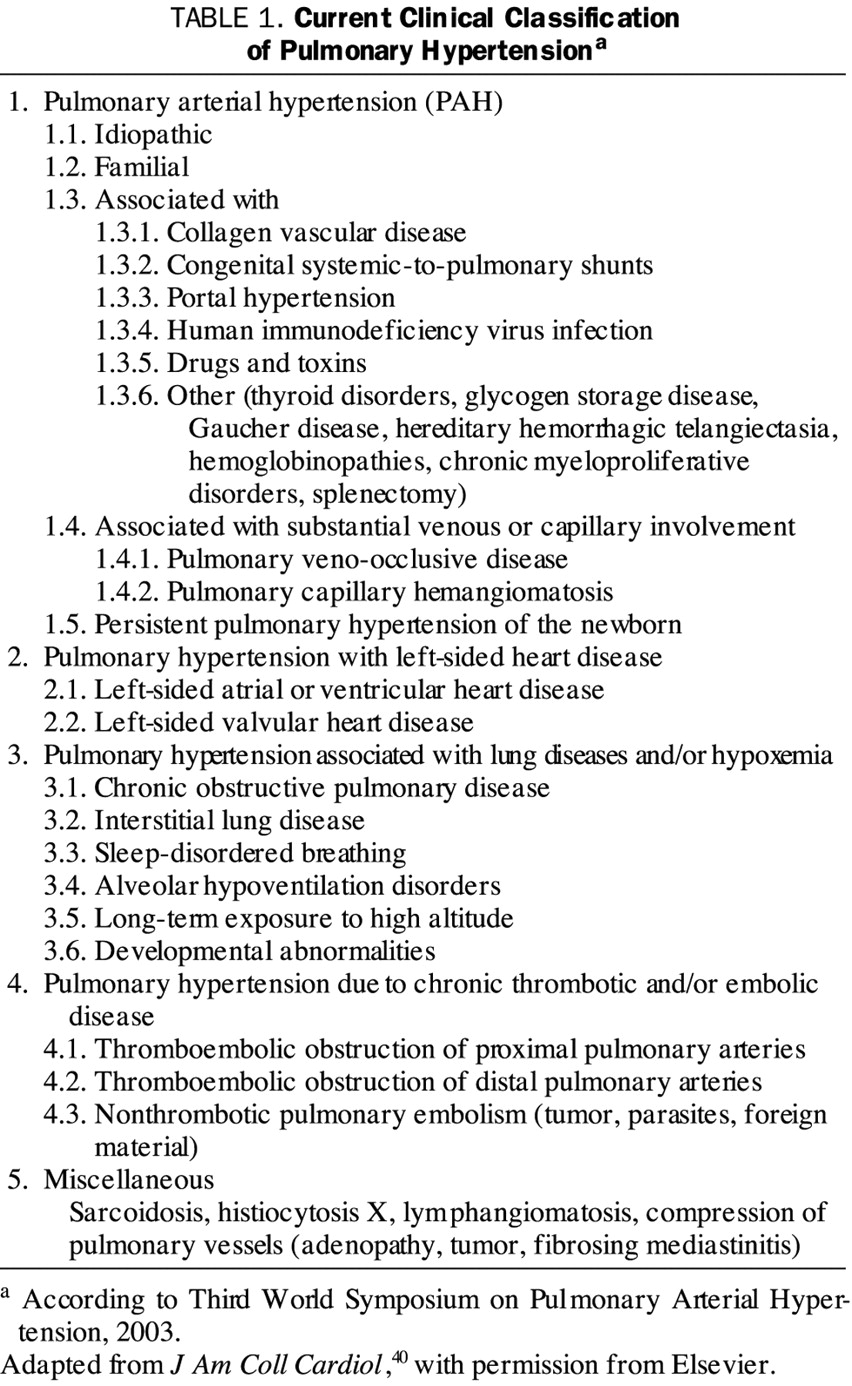

Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension

Diagnostic Evaluation of Pulmonary Hypertension

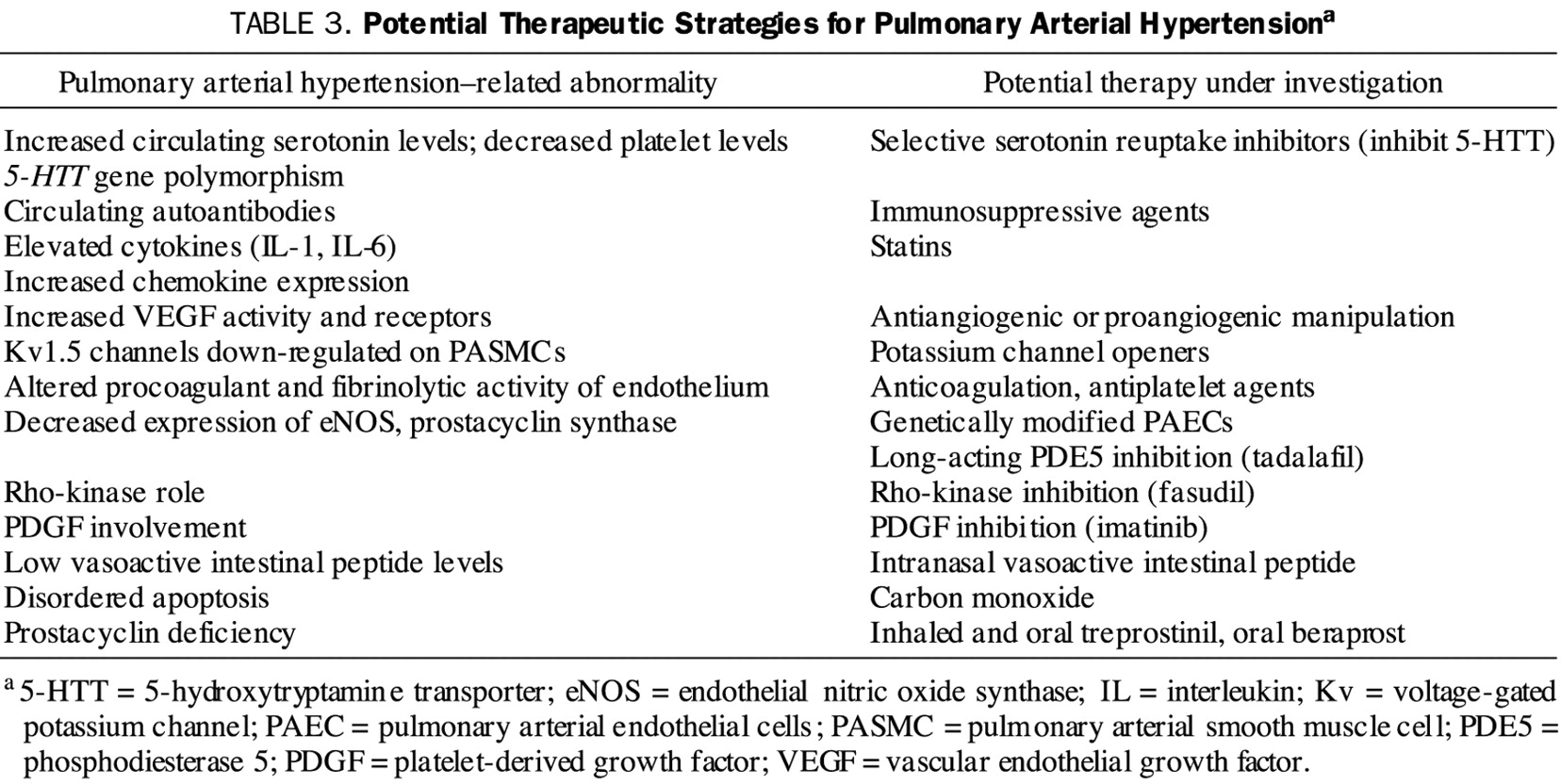

Potential Therapeutic Strategies for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension