RX:

Prostatitis

Acute bacterial prostatitis is a generalized

infection of the prostate gland and is associated with both lower urinary

tract infection (UTI) and generalized sepsis.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis is associated

with recurrent lower UTIs (i.e., cystitis) secondary to areas of focal

uropathogenic bacteria residing in the prostate gland.

The most common cause of bacterial prostatitis is

the Enterobacteriaceae family of

gram-negative bacteria, which

originate in the gastrointestinal flora.

The most common organisms are strains of

Escherichia coli, which are identified

in 65% to 80% of infections. Pseudomonas

aeruginosa, Serratia species,

Klebsiella species, and

Enterobacter aerogenes are identified

in a further 10% to 15%.

Gram-Positive Bacteria: Enterococci are believed to account

for 5% to 10% of documented prostate infections.

The role of other gram-positive organisms, which are also commensal organisms

in the anterior urethra, is controversial.

An etiologic role for gram-positive organisms such as

Staphylococcus saprophyticus, hemolytic streptococci,

Staphylococcus aureus, and other coagulase-negative staphylococci

has been suggested by a number of authors.

A common complication of UTI in men is prostatitis. Bacterial prostatitis is usually caused by the same gram-negative bacilli that cause UTI in females; 80% or more of such infections are caused by E. coli. The pathogenesis of this condition is poorly understood. Antibacterial substances in prostatic secretions probably protect against such infections.

Etiologies of Prostatitis:

A NIH expert consensus panel has recommended classifying prostatitis into three syndromes:

Traditional Classification of Prostatitis Syndromes:

Acute bacterial prostatitis was diagnosed when prostatic fluid was clinically purulent, systemic signs of infectious disease were present, and bacteria were cultured from prostatic fluid.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis was diagnosed when pathogenic bacteria were recovered in significant numbers from a purulent prostatic fluid in the absence of a concomitant UTI or significant systemic signs.

Nonbacterial prostatitis was diagnosed when significant numbers of bacteria could not be cultured from prostatic fluid, but the fluid consistently revealed microscopic purulence.

Prostatodynia was diagnosed in the remaining patients who had persistent pain and voiding complaints as in the previous two categories but who had no significant bacteria or purulence in the prostatic fluid. This clinical differentiation of the prostatitis syndromes is now referred to as the traditional classification system ( Table below ).

| Traditional | National Institutes of Health | Description |

| Acute bacterial prostatitis | Category I | Acute infection of the prostate gland |

| Chronic bacterial prostatitis | Category II | Chronic infection of the prostate gland |

| Category III Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CPPS) | Chronic genitourinary pain in the absence of uropathogenic bacteria localized to the prostate gland employing standard methodology | |

| Nonbacterial prostatitis | Category IIIA (Inflammatory CPPS) | Significant number of white blood cells in expressed prostatic secretions, post–prostatic massage urine sediment (VB3), or semen |

| Prostatodynia | Category IIIB (Noninflammatory CPPS) | Insignificant number of white blood cells in expressed prostatic secretions, post–prostatic massage urine sediment (VB3), or semen |

| Asymptomatic Inflammatory Prostatitis (AIP) | White blood cells (and/or bacteria) in expressed prostatic secretions, post–prostatic massage urine sediment (VB3), semen, or histologic specimens of prostate gland |

* Prostatic pain is usually secondary to inflammation with secondary edema and distention of the prostatic capsule. Pain of prostatic origin is poorly localized, and the patient may complain of lower abdominal, inguinal, perineal, lumbosacral, and/or rectal pain. Prostatic pain is frequently associated with irritative urinary symptoms such as frequency and dysuria, and, in severe cases, marked prostatic edema may produce acute urinary retention.

Physical Examination in Prostatitis Evaluation

Physical examination is an important part of the evaluation of a prostatitis patient, but it is usually not helpful in making a definitive diagnosis or further classifying a prostatitis patient. It assists in ruling out other perineal, anal, neurologic, pelvic, or prostate abnormalities and is an integral part of the lower urinary tract evaluation by providing prostate-specific specimens.

In category I, acute bacterial

prostatitis, the patient may be systemically

toxic, that is, flushed, febrile, tachycardic, tachypneic, and even

hypotensive. The patient usually has suprapubic

discomfort and perhaps has clinically detectable

acute urinary retention. Perineal pain and anal

sphincter spasm may complicate the digital rectal examination.

The prostate itself is usually described as hot, boggy, and exquisitely tender.

The expression of prostatic fluid secretion (EPS) is believed to be totally

unnecessary and perhaps even harmful.

The physical examination of a patient with category

II, chronic bacterial prostatitis, and category III CPPS is

usually unremarkable (except for pain).

Careful examination and palpation of external genitalia, groin, perineum,

coccyx, external anal sphincter (tone), and internal pelvic floor and side

walls may pinpoint prominent areas of pain or discomfort. The digital rectal

examination should be performed after the patient has produced

pre–prostatic massage urine specimens (see later).

The prostate may be normal in size and consistency,

and it has also been described as

enlarged and

boggy (loosely defined by the author

as softer than normal). The degree of

elicited pain during prostatic palpation

is variable and is unhelpful in differentiating a prostatitis

syndrome. The prostate should be carefully checked for prostatic

nodules before a vigorous prostatic massage is performed to produce

prostate-specific specimens (EPS - the expressed

prostatic secretion and post–prostatic massage urine

sample).

In patients presenting with category I, acute bacterial

prostatitis,

a urine culture is the only laboratory

evaluation of the lower urinary tract required.

It has been suggested that the vigorous prostatic massage necessary to produce

EPS can exacerbate the clinical situation, although such fears have never

been substantiated in the literature. A midstream urine specimen will show

significant leukocytosis and bacteriuria microscopically, and culturing usually

discloses typical uropathogens. Blood cultures may show the same organism.

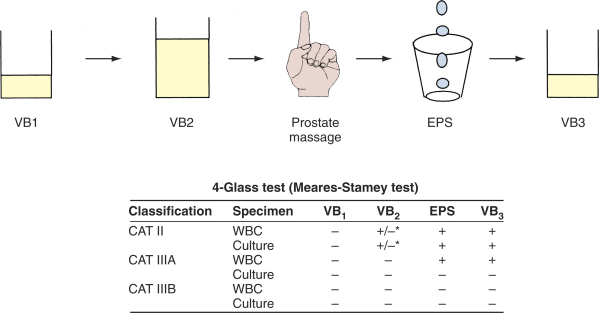

Although the classical 1968 Meares & Stamey four-glass urine collection test (technique) remains the gold standard diagnostic evaluation to distinguish urethral, bladder, and prostate infections of prostatitis patients, numerous surveys have confirmed that clinicians have more or less abandoned this time-consuming and expensive rigorous evaluation.

Technique and interpretation of the Meares-Stamey four-glass lower urinary tract localization test for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

Category II, chronic bacterial prostatitis, is diagnosed if there is a 10-fold increase in bacteria in the EPS or VB3 specimen compared with the VB1 and VB2. In a patient who has acute cystitis, this localization is impossible; and in this case, patients can be treated with a short course (1 to 3 days) of therapy with antibiotics such as nitrofurantoin, which penetrates the prostate poorly but eradicates the bladder bacteriuria. Subsequent localization of bacteria in the post–prostatic massage urine or EPS is then diagnostic of category II prostatitis.

Category IIIA CPPS (chronic nonbacterial prostatitis) is diagnosed when no uropathogenic bacteria are cultured, but excessive leukocytosis (usually defined as more than 5 to 10 WBCs per high-power field [HPF]) is noted in the prostate-specific specimens (EPS or VB3 or both).

Category IIIB CPPS (prostatodynia) is diagnosed when no uropathogenic bacteria are cultured and there is no significant leukocytosis noted on microscopic examination of EPS or the sediment of VB3.

Table -- Suggested Evaluation of a Man with CPPS

Mandatory

Recommended

Optional

Treatment of uncomplicated UTI in men:

Even when seemingly uncomplicated UTI does occur, men should never be treated

with short-course therapy, because of a high rate of early relapse.

Fluoroquinolone

(as: Cipro 500 mg bid) or with TMP-SMX

(Bactrim-DS or Septra-DS1 tab bid) for 7 to 14 days,

assuming the organisms are susceptible.

Treatment of Acute Bacterial Prostatitis:

Fluoroquinolone

(as: Cipro 500 mg bid) for 2 weeks or with TMP-SMX

(Bactrim-DS or Septra-DS1 tab bid) for at least 4

weeks,

assuming the organisms are susceptible.

Recurrence is common and usually connotes a sustained focus in the prostate

that has not been eradicated.

The prostate may harbor calculi, which can block drainage of portions of

the prostate gland or act as foreign bodies in which persistent infection

can reside. An enlarged (and inflamed) prostate gland can cause bladder outlet

obstruction, resulting in pools of stagnant urine in the bladder that are

difficult to sterilize.

Treatment of Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis:

Fluoroquinolone

(as: Cipro 500 mg bid) for 2 weeks or with TMP-SMX

(Bactrim-DS or Septra-DS1 tab bid) for at least 4 to

6weeks,

assuming the organisms are susceptible.

Prolonged treatment with any of these drugs has a greater than 60% probability

of eradicating infection. Most therapeutic failures result from either anatomic

factors or infection by Enterococcus faecalis or P. aeruginosa; these two

organisms are particularly likely to cause relapse after treatment with the

antimicrobial agents currently recommended. Relapses should be treated for

12 weeks. If this therapy fails, long-term antimicrobial suppression or repeated

treatment courses for each relapse are often needed.

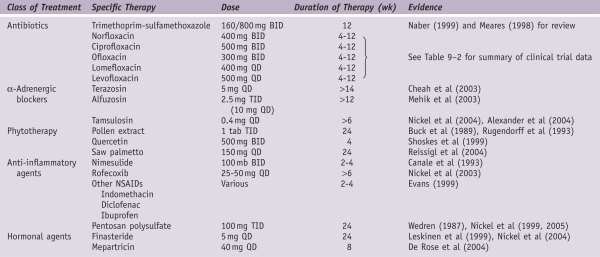

Medical Therapy of Prostatitis

* Multimodal therapy employing multiple concurrent treatment strategies may offer the best results at this time ( Shoskes et al, 2003 ). However, a number of well-controlled prospective studies did not demonstrate increased efficacy by combining ?-adrenergic blockers and antibiotics ( Alexander et al, 2004 ) or Alpha-adrenergic blockers and anti-inflammatory agents ( Batstone et al, 2005). The explanation for this difficulty in treating CP may be that the patients become peripherally and centrally sensitized and treatment targeted to the initiators of the process may not work as well when the condition becomes chronic ( Yang et al, 2003 ).

Others:

Medical Therapy for Chronic Prostatitis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome

* As a rule, only symptomatic UTI requires therapy.

* Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Bacteriuria detected in the absence of symptoms referable to the urinary tract does not warrant antimicrobial therapy except in specific settings. These include during pregnancy, before surgery or instrumentation of the urinary tract, and after renal transplantation. Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients who are immunosuppressed because of transplantation other than renal (i.e., other solid organ or bone marrow) or because of neutropenia has not been well studied and is not currently recommended as standard practice.

In women with diabetes and asymptomatic bacteriuria, a large randomized trial of antimicrobial treatment versus no antimicrobials found no difference in the time to first symptomatic UTI between the groups. The authors conclude that there is no benefit to screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria or treating it in women with diabetes.

* Catheter-Associated UTI

UTIs are the most common nosocomial infections, representing 40% of all such infections. Most nosocomial UTIs are related to bladder catheterization. Catheter-associated UTIs are associated with increased mortality and costs. Multiple risk factors for catheter-associated UTIs have been identified, including the duration of catheterization, lack of systemic antibiotic therapy, female sex, age older than 50 years, and azotemia.57 Risk factors for bacteremia related to catheter-associated UTI are not well established.

Several guidelines can be followed to minimize the occurrence of catheter-related infection [see Table 5]. Most important, the catheter should be inserted with strict aseptic technique by trained persons. In addition, a closed system should be used at all times. Even with optimal care, however, catheter use for 1 month or longer will eventually result in bladder infection. Apparently, little additional protection is provided by antibiotic rinses for the bladder, antibiotic ointments applied to the urethral meatus, and instillation of disinfectants such as hydrogen peroxide into the urinary collection bag. Although systemic antibiotics are of no value when the closed system is to be in place for an extended period, antibiotics may be protective when the catheter is in place for only a few days. However, this advantage should be balanced against the risk of selecting for resistant flora if catheterization must be prolonged unexpectedly. In patients who require urethral catheterization for 2 to 10 days, use of a silver alloy-coated urinary catheter or a nitrofurazone-impregnated catheter may offer some protection against gram-negative organisms infections.

Treatment of catheter-associated UTI depends on

the clinical circumstances.

Symptomatic patients (e.g., those with fever, chills, dyspnea,

and hypotension) require immediate antibiotic therapy [see Complicated UTI,

above]. In addition, it may be useful to remove and replace the urinary catheter

if it has been in place for a week or longer. This eliminates

difficult-to-eradicate organisms in the biofilm on the catheter. In an

asymptomatic patient, therapy should be postponed until the catheter can

be removed. Patients with persistent asymptomatic bacteriuria and those with

lower urinary tract symptoms who have had the catheter removed respond well

to short-course therapy.61

Patients with long-term indwelling catheters seldom become symptomatic unless the catheter is obstructed or is eroding through the bladder mucosa. In patients who do become symptomatic, appropriate antibiotics should be administered, and the catheter should be changed. Therapy for asymptomatic catheterized patients leads to the selection of increasingly antibiotic-resistant bacteria.56,57,60 Thus, although long-term bladder catheterization carries a significant risk of chronic pyelonephritis (10% or more if the catheter is in place for more than 90 days), there is no way to avoid this event other than by catheter removal.62

The appearance of Candida in the urine is an increasingly common complication of indwelling catheterization, particularly for patients in the intensive care unit, on broad-spectrum antimicrobials, or with underlying diabetes mellitus.63C. albicans is still the most common isolate, although C. glabrata and other non-albicans species are also frequently isolated. The clinical presentation can vary from an asymptomatic laboratory finding to sepsis. In asymptomatic patients, removal of the urethral catheter results in resolution of the candiduria in as many as one third of cases. For patients with symptomatic candiduria (fever with or without cystitis symptoms), oral fluconazole, 200 mg/day for 7 to 14 days, has been shown to be highly effective. This regimen was even effective for non-albicans species of Candida that had reduced susceptibility to fluconazole, possibly because of the high concentrations achieved in the urine. For more severely ill patients, the possibility of pyelonephritis and candidemia should be evaluated, and systemic antifungal therapy with fluconazole, 6 mg/kg/day, or amphotericin, 0.6 mg/kg or more a day, should be instituted.

Endoscopy (Cystoscopy)

Clinical experience (rather than controlled clinical studies) suggests that lower urinary tract endoscopy (i.e., cystoscopy) is not indicated in the majority of men presenting with CP/CPPS. However, cystoscopy is indicated in patients in whom the history (e.g., hematuria), lower urinary tract evaluation (e.g., VB1 urinalysis), or ancillary studies (e.g., urodynamics) indicate the possibility of a diagnosis other than CP/CPPS. In these patients, occasionally lower urinary tract malignancy, stones, urethral strictures, bladder neck abnormalities and so forth that can be surgically corrected are discovered. Cystoscopy can probably be justified in men refractory to standard therapy.

Transrectal Ultrasonography of Prostate

Transrectal ultrasonography has become one of the best radiologic methods to evaluate prostate disease and has become an especially helpful clinical tool for the assessment of prostate volume and ultrasound guidance of biopsy needles. The diagnostic value of ultrasonography in differentiating benign from malignant prostate disease is controversial, and the further differentiation of the various benign conditions of the prostate is even more so.

Transrectal ultrasonography can be valuable in diagnosing medial prostatic cysts in patients with prostatitis-like symptoms, diagnosing and draining prostatic abscesses, or diagnosing and draining obstructed seminal vesicles. It is not required in all cases of acute bacterial prostatitis but rather only in those patients who are failing appropriate antimicrobial therapy ( Horcajada et al, 2003 ).

Prostate Biopsy

Occasionally, because of an elevated PSA level or abnormal digital rectal examination, prostate biopsy is indicated. Some clinicians will consider starting patients with elevated screening PSA levels and a history of prostatitis or symptoms of CPPS on antibiotics, but this practice is really only rational in patients with acute or chronic bacterial prostatitis, conditions that invariably lead to elevated PSA levels. The diagnosis of CP/CPPS should only be used as a reason against a prostate biopsy if the clinician is looking for an excuse not to biopsy.

Out of desperation, urologists sometimes resort to prostate biopsy in an attempt either to demonstrate histologic evidence of prostatic inflammation or to culture an organism that cannot be cultured employing the standard approach. The importance and interpretation of prostate biopsies in CP performed for reasons other than prostate cancer screening is unclear.

Hematospermia

Hematospermia refers to the presence of blood in the seminal fluid. It almost always results from nonspecific inflammation of the prostate and/or seminal vesicles and resolves spontaneously, usually within several weeks. It frequently occurs after a prolonged period of sexual abstinence, and we have observed it several times in men whose wives are in the final weeks of pregnancy. Patients with hematospermia that persists beyond several weeks should undergo further urologic evaluation, because, rarely, an underlying etiology will be identified. A genital and rectal examination should be done to exclude the presence of tuberculosis, a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and a rectal examination done to exclude prostatic carcinoma, and a urinary cytology done to exclude the possibility of transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate. It should be emphasized, however, that hematospermia almost always resolves spontaneously and rarely is associated with any significant urologic pathology.

(REF: Wein: Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9th ed. 2007)